The California Gold Rush

Published by Sam Jacobs on 09/29/20

The California Gold Rush is, forgive the pun, the gold standard of gold rushes in the United States. Indeed, California is known as the “Golden State” both because of its beautiful natural scenery, but also because of this gold rush that absolutely changed the face of American history in a short period of time. A great way to explain the changes is to compare California before the gold rush — a sparsely populated area inhabited mostly by Native Americans and Mexicans — to a state important enough that the first Republican Presidential candidate, John C. Fremont, hailed from the state.

It all began on January 24, 1848, when James Marshall, a sawmill entrepreneur, and carpenter, discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California – located on the South Fork American River in the knolls of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Sutter’s Mill is in the northern central portion of the state, 48 miles from what is now Sacramento. California was still technically a part of Mexico at this time, as the Mexican-American War was still underway, but it had been claimed by the United States since the Bear Flag Revolt in 1846. When all was said and done, 300,000 people had poured into the region and the population demographics of the territory — a state by 1850 — were changed forever. Tens of billions of dollars were extracted from the mines in the state, which helped the United States on its road to becoming an economic powerhouse.

Who Was James W. Marshall?

As is often the case with a gold rush, the California Gold Rush had very inauspicious beginnings. James Wilson Marshall didn’t own the land where he discovered the gold and thus joins the long list of people who came close to grabbing the golden ring but were unable to do so due to circumstances outside of their control.

The land itself was owned by John Sutter, born Johann August Sutter, an immigrant from one of the many small states that made up the Holy Roman Empire. Marshall was examining a channel on the land when he noticed the shiny flecks that often meant there were large deposits of gold. For his part, Sutter was far more concerned with the completion of his sawmill than he was with panning for gold, so he simply allowed the workmen to hunt for gold on his land in their spare time.

Ironically, the discovery of gold on his land led to Sutter’s economic ruination. Though he attempted to keep the find quiet, the discovery of land was exposed to a mass audience by newspaper publisher Samuel Brannan. When gold fever spread throughout his crew, they all left the steady work of building a sawmill to hunt for gold. Eventually, the hordes of prospectors drove Sutter off of his own land. His son, John Augustus Sutter Jr., had no small success rebuilding the land, but the prospectors destroyed virtually everything of value that lay on the land. The elder Sutter eventually received a $250 monthly pension as reimbursement for his land.

The expensive precious metal find lead directly to the founding of Coloma, the gold mining camp that grew into the first mining town in California. The boomtown saw great success while the California gold rush was in action, being lucky enough to happen in a period lacking in mining companies. However, in the time post-gold rush, Coloma is little more than a ghost town. The town resides within what is now the Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park.

Marshall, too, was economically ruined by the army of squatters who destroyed crops and cattle as they went. However, he returned to business in Coloma in 1857, running a vineyard that saw some success in the 1860s before being ruined by higher taxes and increased competition. He then returned to prospecting, which was largely unsuccessful. He died broke in a cabin on August 10, 1885. A monument was eventually erected to him and visitors can still go see the cabin where he spent his final days.

Going to San Francisco

It bears repeating that going from a “western” American city of the time, such as St. Louis, to California, was not anywhere near as easy as it is today. Indeed, there was not even rail transportation out to California at this time. And it was the California Gold Rush that changed all of that.

Most of the 49’ers, in fact, didn’t even travel over the land. They got to California by sea. Remember that this was prior to the construction of the Panama Canal. The journey went all the way around Tierra del Fuego and took between four and five months. That was a total of 18,000 nautical miles (21,000 land miles or 33,000 kilometers). The other option was to go to the thinnest part of Panama, cross the jungle, and pick up another boat on the other side. Companies such as the U.S. Mail Steamship Company, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (which enjoyed federal subsidies), and the Accessory Transit Company allowed for men who weren’t prospecting to make their fortunes off of the California Gold Rush.

Of course, some adventure and treasure seekers did use an overland route, with most utilizing the California Trail, a 3,000-mile trail that ran from the Missouri River to California. It was one of a series of so-called “pioneer trails” that were built by enterprising settlers on their way out west during the 19th Century.

Supplies were likewise needed in California, but it was difficult to keep crews because men generally deserted to go hunt for gold in the fields. Some abandoned ships were converted into warehouses, taverns, hotels, and other structures, including at least one jail. But when all was said and done, it was the merchants who made out like bandits during the California Gold Rush, not the miners.

Who Were the Forty Niners?

The Forty Niners

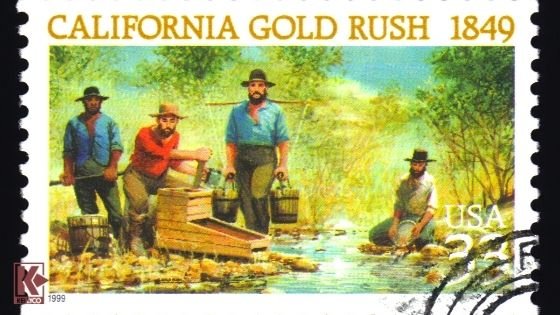

The forty niners were much more than just a San Francisco football team. They were the movement of aspiring gold miners who moved west seeking their fortune in the goldfields of California. It was the actual residents of California who made the first strikes beginning in 1848. The forty niners were those who came later in search of any gold nuggets that might be left.

The next group of treasure seekers were men from the area surrounding California. This makes sense, as it was in these regions where word of the gold first spread to. The first major emigration to the gold region of California came from Oregon, via a trail that rains directly from the Beaver State to the Golden State. These “48’ers” as they were called were among the most prosperous of prospectors, able to gather thousands of dollars worth of gold every day. Even the average prospector was making 10 to 15 times what laborers were making back on the East Coast.

The forty niners themselves were mostly, but not entirely, from America. People were coming from as far away as the antipodes to hunt for gold. Latin America, Mexico in particular, provided much of the manpower that would attempt to find a fortune in California. The European Revolutions of 1848 likewise provided a steady stream of adventurers looking to strike it rich, primarily from France, but also from Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

All told, it’s estimated that 90,000 souls arrived in California in 1849 alone, half of them taking an overland route and half of them coming by sea. It is further estimated that a relatively scant 40,000 to 50,000 of these gold seekers were American, the rest coming from abroad. Fewer than 4,000 of these were African American, most from the United States, but also some from countries in South America like Brazil and Peru. The arrival of some 20,000 immigrants from China seeking gold led to both the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Foreign Miners Tax. And while there were some women, their numbers were hardly significant — a scant 700 or so women went west to the California goldfields, most of these wives and prostitutes.

Lawlessness and Property Rights

The problem with a weak rule of law and a lot of gold sitting around is that property rights quickly become difficult and complicated to enforce. This is a theme that runs throughout all of the gold rushes and the California Gold Rush is no exception. This was not helped by the strange, nebulous relationship of what would later become the State of California to the United States.

California Gold Rush

At the time of the Gold Rush, California was not a part of the United States at all, it was simply under the control of the United States military thanks to the Mexican-American War. Indeed, California was never a territory in the way other Western states were. It went from a military-occupied area with a “provisional government” in 1846 to being granted statehood in 1850 with no status as a territory in between.

All of this means that there was never any degree of civil control or traditional rule of law during the period of the California Gold Rush. No legislature, no executive, and no judiciary existed until California became a state in 1850. The result of this meant that the actual law as it was applied was a curious mixture of Mexican law, American values, and whatever you could get away with.

Possession was ten-tenths of the law. Any gold that you could carry away, you kept, regardless of what the law said or whether or not someone else might have held title to the land. Even the end of the war didn’t do much to alleviate this situation. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War, recognized Mexican land grants as valid. However, this was a very small portion of the land ceded to the United States. The remaining land was considered “public land.” Thus, anyone was allowed to mine for gold on it — and oftentimes “anyone” did.

The miners eventually came up with a system that more or less worked. Gold claims were only good as in as much as they were actively being worked. This allowed prospectors to “claim jump,” or work an area to find out if it was worth continuing to work before jumping on to the next spot. Oftentimes, prospectors would go to an area that another prospector had already worked on, piggybacking off of their labor and hoping to have more luck than the last guy.

The California Gold Rush and Technology

Pure Gold

Silicon Valley isn’t the first time that California has led innovation and technology in the United States. The California Gold Rush led to a giant boom in mining technology, the effects of which are still with us today.

Early forty niners were able to use panning for gold and placer mining to get rich. This is because there were such rich deposits of gold in the state that there was a lot of low-hanging fruit as it were. But this is not a reliable method of extracting large amounts of gold from a region. It only allows for very easy pickings. And once people saw the riches that could easily be panned out of the rivers in California, they wanted to see what they could get if they dug a little deeper.

Modern hydraulic mining was first developed in California specifically for this purpose around 1853. By the mid-1880s, about 11 million ounces (340 tons) of gold (or about $19.8 billion in September 2020 prices) had been recovered by this new hydraulic mining process. Dredging for gold was likewise invented in California after the initial Gold Rush had died down. Hard rock mining also saw massive innovations as the search for gold in California became more and more challenging.

It’s not a stretch to say that, without the California Gold Rush, there might not have been a massive move to California during the 19th Century. Indeed, to this day, California might remain a rural backwater more known for growing oranges and almonds than anything else if there were no gold there. This underscores just how important gold is to the history of American Westward Expansion.

It was the California Gold Rush that made San Francisco the first West Coast city to crack the top ten in terms of population in the 1870 census, a place where it remained until the 1900 census, rising as high as the eighth-largest city in the United States. The mark of the California Gold Rush can still be seen on the Golden State, with references to it virtually everywhere, including the famous Golden Gate Bridge.